’s take that china will attempt to calmly manage the decline of amerikkkan empire feeling more prescient daily.

’s take that china will attempt to calmly manage the decline of amerikkkan empire feeling more prescient daily.where’s that from? Years ago I read Debt, BS jobs, and dawn of everything and enjoyed his writing style even if I thought some ideas were idealistic.

the very end of Debt if memory serves

It is a very sober take. Complete breakdown of American Hegemony from one moment to the next would really hurt China’s plans to continue developing, it’s better to just keep it at a manageable rate.

it is an ultimately sober take. my initial response to it of uncertainty is because graeber’s reasoning strikes me as somewhat Orientalist in nature. but regardless, he does effectively seem to be right. passage reproduced below for clarity.

[I]t’s never clear whether the money siphoned from Asia to support the U.S. war machine is better seen as “loans” or as “tribute.” Still, the sudden advent of China as a major holder of U.S. treasury bonds has clearly altered the dynamic. Some might question why, if these really are tribute payments, the United States’ major rival would be buying treasury bonds to begin with – let alone agreeing to various tacit monetary arrangements to maintain the value of the dollar, and hence, the buying power of American consumers. But I think this is a perfect case in point of why taking a very long-term historical perspective can be so helpful.

From a longer-term perspective, China’s behavior isn’t puzzling at all. In fact, it’s quite true to form. The unique thing about the Chinese empire is that it has, since the Han dynasty at least, adopted a peculiar sort of tribute system whereby, in exchange for recognition of the Chinese emperor as world-sovereign, they have been willing to shower their client states with gifts far greater than they receive in return. The technique seems to have been developed almost as a kind of trick when dealing with the “northern barbarians” of the steppes, who always threatened Chinese frontiers: a way to overwhelm them with such luxuries that they would become complacent, effeminate, and unwarlike. It was systematized in the “tribute trade” practiced with client states like Japan, Taiwan, Korea, and various states of Southeast Asia, and for a brief period from 1405 to 1433, it even extended to a world scale, under the famous eunuch admiral Zheng He… All this was ostensibly rooted in an ideology of extraordinary chauvinism (“What could these barbarians possibly have that we really need, anyway?”), but, applied to China’s neighbors, it proved extremely wise policy for a wealthy empire surrounded by much smaller but potentially troublesome kingdoms. In fact, it was such wise policy that the U.S. government, during the Cold War, more or less had to adopt it, creating remarkably favorable terms of trade for those very states – Korea, Japan, Taiwan, certain favored allies in Southeast Asia – that had been the traditional Chinese tributaries; in this case, in order to contain China.

Bearing all this in mind, the current picture begins to fall easily back into place. When the United States was far and away the predominant world economic power, it could afford to maintain Chinese-style tributaries. Thus these very states, alone amongst U.S. military protectorates, were allowed to catapult themselves out of poverty and into first-world status. After 1971, as U.S. economic strength relative to the rest of the world began to decline, they were gradually transformed back into a more old-fashioned sort of tributary. Yet China’s getting in on the game introduced an entirely new element. There is every reason to believe that, from China’s point of view, this is the first stage of a very long process of reducing the United States to something like a traditional Chinese client state. And, of course, Chinese rulers are not, any more than the rulers of any other empire, motivated primarily by benevolence. There is always a political cost, and what that headline marked was the first glimmerings of what that cost might ultimately be.

new emoji material

just submitted it

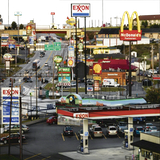

When do we get treaty cities? I want to move to one.

treaty cities

I read that as treatler cities, and I thought “huh, America already has plenty of those”

opening a bund in manhattan or whatever, the best real estate in the city, and now only chinese law applies there, and anglos have to wait tables and perform anti-anglo racist cabarets while tuhaos and cpc dangyuans watch and throw around 100Y bills

I, for one, welcome Hanseatic League 2: Electric Boogaloo.

A miniso opened up near me, and I live in the ass end of nowhere. China, please colonize me more.