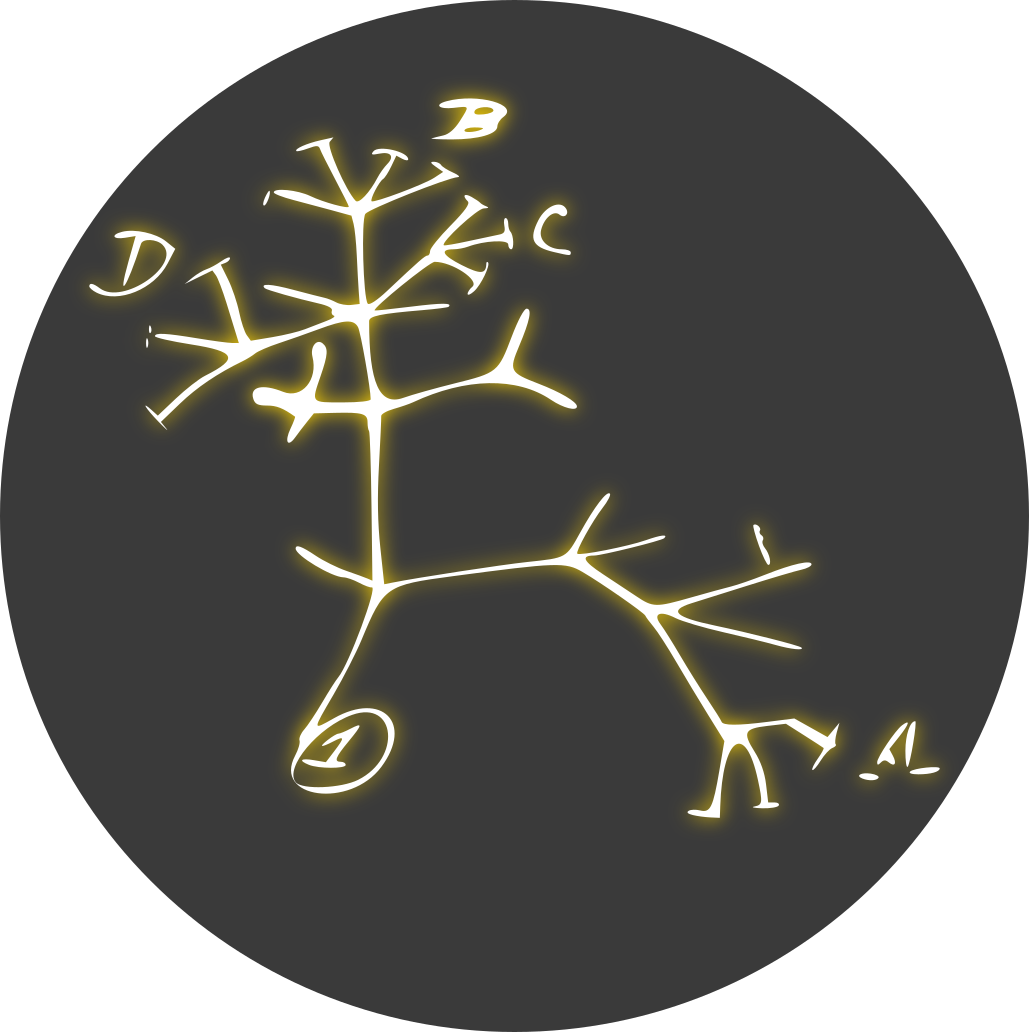

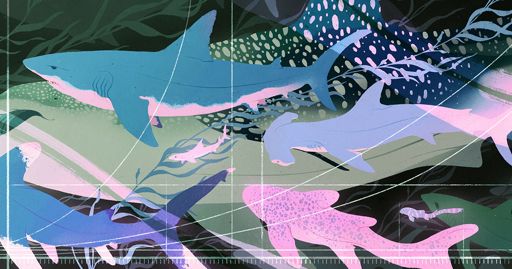

It’s a universal fact that as any 3D object, from a Platonic sphere to a cell to an elephant, grows outward in all directions, its total surface area will increase more slowly than the space it occupies (its volume). If the object’s geometry and shape remain the same as it gets bigger, then its surface area will increase roughly as fast as its volume to the two-thirds power. For centuries, biologists have wondered if life forms, too, follow this two-thirds scaling law, even though they come in a stunning variety of shapes and sizes. If so, it would suggest that there are underlying constraints fundamental to evolution that might influence how life interacts with the world around it.

I read the article, but I can’t help but think I’m missing something. Isn’t it obvious that this would be the case? I understand that testing assumptions is a good thing for science and have no quibble with the research itself, but was this really wondered about for centuries or is that just compelling reporting? If so, what made people wonder if life forms, unlike everything else, weren’t subject to this proportion of scaling?

I didn’t bother reading it but I presume an attempt at compelling reporting. Mice and elephants have some morphological differences that are influenced by their size differences and these have been used to explain some high school physics for at least decades but I presume longer

(like the internal volume to surface area ratio meaning the elephant has issues dissipating heat and thats part of the function of their ears, or how the elephants legs are stocky and below them but smaller animals don’t even need their legs below them)